Inquiry Formation

This is an intermediate page for formation materials. Just press the “+” sign at the far right of the section you wish to see below. At the bottom of this page are links to PDFs for each of the individual modules.

Orientation and Intro

We welcome you today for the first stage of Formation in the Lay Dominicans. This first year is known as “Inquiry”. For the next year you will be learning the fundamentals of the Order of Preachers (Dominicans). It is only the beginning of a lifetime of continuous learning. Fundamentally, Dominican life is centered on four “Pillars” (key characteristics of the Order that make the Dominican Order what it is): Community, Prayer, Study, and Preaching. Upon the completion of the Inquiry year, the Formation Director will present to the Chapter Council a list of Inquirers who qualify for reception into the Order. If the Chapter Council is in agreement, then the Inquirer receives the Dominican pin (usually in a reception ceremony) and begins the next phase of formation, “Candidacy”.

For one year, the Candidate attempts with the help of God and the Chapter to be formed as a Dominican. At the end of this year, the Candidate asks to make Temporary promises for three years. The new Temporary Promised is given the Dominican Scapular and the Rule and Directory of the Chapter.

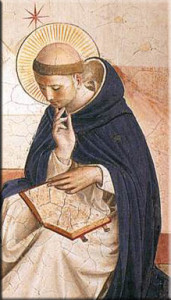

The Lay Dominicans are a part of the world wide Order of Preachers, otherwise known as the Dominican Order. In some areas Dominicans are also known as “black friars” because of the black cloak and Cappus that the Friars and religious wore for travel and during Lent.

The Order had its beginnings in 1203 when St. Dominic of Guzman was sent with his bishop to arrange a marriage between the son of the king of Castile and the daughter of the Lord of the Marches. While traveling through southern France, Dominic was appalled at the major inroads a heresy known as Albigensianism was making in that part of the world, (so called because it started in the town of Albi). Albigensianism taught that all matter was evil and all spirit was good, and that the “good” God created the spirit realm while a demon god created and reined over the corporal world. This meant that all material things and pleasures had to be rejected.

The “Elect” of their society lived strictly, while everyone else could do whatever they desired , as long as they accepted all Albigensian teachings as true. They had to renounce the Catholic faith and , instead, admire and respect their Elect.

As soon as his mission was completed, and with permission, St. Dominic resolved to return to Southern France and endeavored to counteract this heresy with the preaching of the truth. It must be remembered that at this time it was not common for any priest to preach – only the Pope and bishops could preach. Dominic began to attract many men and lay people to him. The lay people at first were known as the “Militia of Christ,” and would soon be given a rule and become known as “The Order of Penitents”. This was the beginning of the “Third Order” or more commonly known today as Lay Dominicans, which is now the largest branch of the Order.

As time went by, Dominic realized that it was not just Southern France that needed the preaching of the truth, but rather the entire world. With the approval of the Holy See, Dominic began to assemble a band of well-educated men to be itinerant preachers. Eventually they were to become the Order of Friars Preachers. He dedicated the Order to preaching, winning souls for Christ. St. Dominic placed great emphasis on study. A preacher had to be educated to know what he was talking about before he got into the pulpit. Another characteristic of the Order that was even more innovative for the time was the democratic spirit of the Order. All superiors were to be elected for certain limited terms, and laws were to be made by elected delegates. It is this democratic characteristic that has allowed the Dominican Order, of all the major religious Orders, the ability to be able to reform itself from within – the Domincan Order has never split into several different Orders, as have the benedictines who are in several groups (Trappists, Cistercians, and regular Benedictines), or the Franciscans (who are Conventuals, Capuchins, and Minors), or the Carmelites (who are either Calced or Discalced).

At about the same time as St. Dominic was gathering a group of men around him to be the nucleus of the Order, he also founded a monastery of cloistered nuns in Prouille near Toulouse. Most of these were women who had been Albigensians, but who had returned to the Church and wanted to continue to serve God in some kind of Catholic religious life. Thus, the Friars, the Laity and the nuns came into being at roughly the same time.

The Dominican Order or Family is worldwide and is composed of various branches. First are the Friars. Second are the cloistered nuns, living in monasteries. Third are diocesan priests and apostolic Sisters/Brothers (Third Order Regular/Religious). Lay Dominicans are Third Order Secular, living in the secular world, not in a conventual setting.

The head of the Order is known as the Master of the Order. He has direct jurisdiction only over the Friars, Nuns, and Laity. The convents of Dominican Sisters are under Pontifical jurisdiction. Each convent has a Superior.

In the United States, there are four Dominican provinces: Eastern, Central, Southern, and Western. There are Lay Dominican Chapters located in each Dominican Province.

The units of Lay Dominicans are called Chapters. In the Southern Province, the Chapters are lead by a Moderator. The Chapter elects a Council which conducts the business of the Chapter. When necessary or desirable, a council’s decisions are presented to the entire chapter for approval or input. Following the tradition of the Friars, all the officers including the members of the Council are elected directly by the Chapter. Chapters typically meet once a month. At the provincial level, there is also a Lay Provincial Council which meets annually.

Becoming a Lay Dominican is not like joining a club, a sodality, or even a Confraternity. One is joining a Religious Order, and becomes a Dominican in the fullest sense of the term to be taken very, very seriously. Inquirers and Candidates receive a period of formation. They make public promises to live according to the Dominican spirit and the Rule and Directory of the Chapter.

History of the Dominican Order

LAY DOMINICANS ARE MEMBERS OF A WORLDWIDE FAMILY

The Dominican Family was founded by St. Dominic de Guzman, a Spanish priest born in Caleruega in 1170. In 1203 he organized his traveling preachers and founded the Dominican “Order of Preachers” (the meaning of the OP that you see after a Dominican’s name). Dominicans all over the world continue to draw upon the charisms of St. Dominic and are formed throughout their entire lives according to the priorities and fundamentals of the Dominican way of life. There are four principal branches of the Order, all true members of it:

The Friars: the brothers and priests who profess solemn vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience and who may be involved in a variety of ministries. All serve the primary role and ministry of the Order: preaching. Like the other branches, the men dedicate their lives to prayer, study, and community life in order to carry out the priorities of the Order, preaching and care of the poor.

The Laity: men and women from all walks of life who commit themselves through formal profession to the Dominican way of life integrated into their established life styles, sharing in the charism and priorities of the Order.

The Nuns: women who live intense lives of prayer in monasteries, profess solemn vows, and participate in the mission of the Order from their cloisters.

The Sisters: women who profess the simple vows and live active apostolic lives along with the prayer and community life that is the hallmark of Dominicans.

Binding all of these branches together is the common love for the Church and the Order, commitment to the mission of preaching, and devotion to prayer (especially the Liturgical prayers of the Hours and the Mass).

LAY DOMINICANS STRIVE TO LIVE THE CHARISM OF THE ORDER

Prayer: a faithful regimen of daily prayer: daily Mass, the Liturgy of the Hours in the morning, in the evening and before bed, personal meditation, particularly of the Scriptures, and the Rosary are essential elements of Dominican Spirituality. In addition, a yearly retreat, preferably in community, is considered essential for remaining centered and committed to the Christian and Dominican vocation.

Study: a vigorous seeking after truth, especially in Scripture, Church documents, and writings of the saints and theologians, lead the Dominican to greater truth. The principal part of the meetings of the Laity is the organized study program in which all participate and for which all prepare.

Works: a willing and cheerful fulfillment of apostolic work such as ministry to the poor, the marginalized, the unfortunate, the sick; preaching as the opportunity arises and in accord with the station in life of the lay Catholic and Dominican, the example of a joyful and moral life, readiness to enter into dialogue with the unbelievers or faith-troubled, eagerness to witness to the Good News.

Community: an empathetic eagerness to enter into the relationship of brothers and sisters in our father Dominic, to gather for support, encouragement, and appreciation of one another, to study and pray together, and to accept the obligations of belonging to a cohesive group.

LAY FRATERNITIES AND THIRD ORDERS IN THE CHURCH

When we speak about Lay Fraternities and Third Orders in the Catholic Church, we generally mean lay members of religious orders. The Dominicans, Franciscans, Benedictines, Norbertines, Carmelites, and Missionaries of Charity are all examples of

Page 5

orders in the Church who have lay branches, although each order may have a different way of referring to its lay members. (For example, in the Dominican Order, we are called lay Fraternity members, or tertiaries. In the Missionaries of Charity, lay cooperators are called coworkers. It should also be noted that some orders receive professions from those in their lay branch, as with the Dominicans, while others simply invite laity to participate fully in the living of the order’s charism without making professions.)

Lay men and women in the Fraternities of St. Dominic do not necessarily live in community with each other but practice many of the same spiritual disciplines of the religious of that order. Any Catholic in good standing may join these associations.

The Beginnings of the Fraternities of St. Dominic

In the early days of the Dominican Order, neither St. Dominic nor the early Preachers desired to have under their jurisdiction-and consequently under their responsibility-either religious or lay associations. During his life, then, St. Dominic never wrote a rule for the Fraternities. Instead, it happened that a large body of laity who were living a life of piety found themselves attracted to St. Dominic and his initiative; they grouped themselves around the rising Order of Preachers and constituted on their own a “third order.”

In 1285, the need for more firmly uniting these lay people to the Order of Preachers and its direction led the seventh Master General, Munio de Zamora (at the suggestion of Pope Honorius IV) to devise a rule known as “The Third Order of Penance of St. Dominic.” Pope Honorius IV granted this new fraternity official Church recognition on Jan. 28, 1286.

In the rule written by Munio de Zamora, some basic points are: 1) the government of the Dominican Fraternities is immediately subject to ecclesiastical authority; 2) in the spirit of St. Dominic, those in the Fraternities should be truly zealous for the Catholic faith; 3) Fraternity members visit sick members of the community and help them; 4) Fraternity members help others through their prayers.

After the Fraternities of St. Dominic got off the ground, it drew many new members. Its fraternity in Siena especially flourished. Among the list of members of that fraternity was she who would become St. Catherine of Siena. Wherever the Dominican Order spread throughout the world, the fraternity chapters spread with it.

Further Information about Dominican History

The original purpose behind the Fraternities of St. Dominic was the preaching of penance. However, over time the Fraternities began to stress the importance for lay Catholics of having strong, solid formation in their faith. The Fraternities became, and continues to be, a group that strives to know their faith and to be well-formed and competent in sharing that faith with others. Persuasive communication of Catholic truth to the secular world is perhaps the most pressing mission of the Fraternities of St. Dominic.

We should mention too that, at its conception, the Fraternities served the Church in a military capacity, defending her from opposition. Now, certainly, Third Order Dominicans do not serve militarily but instead defend the Church from error through preaching and teaching the truth about Catholicism.

St. Catherine of Siena is the patroness of the Fraternities of St. Dominic. Following her example, Dominican tertiaries have always shown special devotion to the Church. Also in imitation of their patroness, who wrote profound mystical works and emphasized the truth of Catholic teaching in all of her letters, Fraternity members labor to know well their faith and to articulate it to others with persuasion.

Several saints and blessed in the Church have been in the Fraternities, including St. Catherine of Siena, St. Rose of Lima, Bl. Pier Giorgio Frassati, and St. Louis de Montfort.

Meeting 1

The Place of Study In the Ideal of St Dominic

by James A. Weisheipl, OP

The purpose of the Dominican Order is stated clearly and simply in the Constitutions:

Our Order is known from the beginning to have been specially instituted for the sake of preaching and the salvation of souls. Consequently our study must aim principally at this, that we might be useful to the souls of others.1

This statement of purpose is taken almost verbatim from the earliest extant constitutions, which goes on to say that in view of this end

the prelate is to have authority to dispense brethren in his own convent from these [constitutions] when it seems to him expedient to do so, particularly in those matters which seem to impede study or preaching or the good of souls.2

The essential means for attaining the special aim of the Order are explicitly stated in our modern constitutions as follows:

The means, established by the most holy Patriarch for reaching our goal, are: besides the three solemn vows of obedience, chastity and poverty, the regular life with its monastic observances, the solemn recitation of divine office, and the assiduous study of sacred truth.3

These means, we are told, may not be abandoned or substantially changed without changing the character of the Dominican Order, although, the vows excepted, they may be opportunely tempered (temperari) to a certain extent (aliquatenus) by the demands of the age or circumstances, provided that these four means are rendered more apt for attaining the goal of preaching and the salvation of souls. These four means, namely solemn vows, monastic life, choral office and study, are not classified as such in the Constitutions of 1228, 1238 or 1241. But no one could doubt that the four essential means are implied throughout the entire text of the primitive rule. The unique character of St. Dominic’s Order lies in the special goal of preaching plus the four essential means.

For us in the twentieth century there is no difficulty in understanding the importance of solemn vows in the Dominican Order. The counsel of Christ to leave all things and follow Him is the very cornerstone of all religious life. This surrender, confirmed by vows having special canonical effects, makes the existence of an Order possible. Similarly it is not difficult for us in the twentieth century to appreciate the importance of a common life according to a recognized rule. Without a stable rule of life regulating procedures, order and obligations, it would be impossible for men (or women) to live in religious peace. Likewise it is not difficult for twentieth century Dominicans to appreciate the value of the choral recitation of the divine office. Modern religious institutes have generally abandoned the choral recitation of the office. Twentieth century Dominicans, however, find no difficulty in accepting the ancient practice as a means of personal sanctification and of giving public glory to God. It is fitting that those who live together with one mind should pray together with one heart.

In the case of study, however, it is not so easy in the twentieth century to appreciate the place of study in the ideal’s of St. Dominic. Since the Council of Trent a great number of seminaries have been established, seminaries with a high standard of academic excellence. Today every secular priest has had the benefits of some college education, two or three years study of philosophy and four years of theology. Every religious Order and Congregation engaged in the training of priests must meet the academic standards of Rome. What, then, makes study so special in the Dominican Order? Perhaps St. Dominic merely anticipated the modern seminary. Perhaps today study does not occupy the same position in the Dominican ideal as it did in the thirteenth century when so few of the clergy were educated. Moreover, the modern standard of living, particularly in the United States, would seem to diminish the importance of study in the Dominican Order. Today the majority of the laity have had at least a high school education, and not a few are eminent scientists, scholars and writers. The facility with which learning can be acquired through the printed word has been increased by the radio, television and the silver screen. It would seem, then, that study does not occupy the same place in the Dominican ideal as it did in previous centuries.

In this brief paper I wish to clarify the precise place of study in the ideal of St. Dominic. I will not say anything about the actual status of study in the Order, or about its appreciation in this or that Province of the Order. I wish to concentrate on study, the fourth essential means of attaining the goal of the Order, as understood by St. Dominic and the brethren of the early thirteenth century. So often when a Dominican thinks of study, he thinks immediately of St. Thomas, and perhaps exclusively so. In this paper I wish to focus attention on the period preceding St. Thomas. Such a focus may help us to appreciate more fully the Dominican spirit of the Angelic Doctor.

First we will examine the historical facts; then we will try to analyze them for a better understanding of the place of study in the ideal of St. Dominic.

I

The intellectual character of the Order stems from Dominic himself and the needs of the early thirteenth century.

The intellectual and cultural renaissance of the twelfth century were beginning to change the face of Europe by the turn of the thirteenth century, but this change was slow. Centers of learning such as Paris, Oxford, Bologna and Padua were beginning to take the place of monasteries and Cathedral schools, but these centers were small and few in number. Contact with the wealth of Arabic culture had been made in Spain, and commerce with the Greeks opened new horizons in Sicily and Venice. But only a few scholars had the opportunity of transmitting this learning to eager students. The intellectual level of the secular clergy was generally low, and it was outside the competence of monks to elevate it. In the spirit of Saints Isidore and Leander, Cassian and Pope St. Gregory the Great, monks of every sort were forbidden to study secular literature; whatever learning was encouraged in the monasteries was supposed to be limited to personal meditation on the Bible and private reading of the Fathers. Clerics, on the other hand, both secular and regular (i.e. the Canons Regular), had an obligation to acquire a modicum of learning both secular and divine in order to fulfill the functions of their office. Bishops, of course, were the official teachers of sacred truth, but there were too few bishops sufficiently learned and zealous for the apostolic office. At the beginning of the thirteenth century Pere Mandonnet has estimated, 4 there were no more than a dozen masters of theology outside the universities actually teaching sacred doctrine. It is not surprising that the Cistercian monks, the secular clergy and even the local bishops were unable to cope with the new intellectual heresies of Albigensianism, Waldensianism and Catharism, which took root in Southern France and Northern Italy.

Onto this scene came Dominic of Guzman. Born in 1170 at Caleruega in Northern Castile, he received his elementary training from a certain uncle, an archpriest. About the age of 14 Dominic was sent to the nearby city of Palencia to study the liberal arts. Bl. Jordan tells us that at that time there flourished a studium of arts in that city.5 After studying the arts Dominic enrolled in the Cathedral school at Palencia, where he “spent four years in sacred studies.”6 Dominic had a great love for books and he annotated them carefully.7 It was not easy for him to sell his books to help the poor during the famine, but his example inspired fellow theologians and even masters of theology to follow his liberality.8 As a secular priest, and later as archdeacon of Osma (1199) and a member of the Cathedral Chapter which had recently embraced the rule of Canons Regular, he pursued a life of ardent prayer and assiduous study. 9

Dominic was about 35 years old when he accompanied the learned and zealous Bishop Diego into the heretical territory of Southern France. We are told that he sat up all night in theological discussion with an Albigensian inn-keeper, a discussion which ended in the conversion of the heretic.10 Between 1205 and 1208 the itinerary of St. Dominic can be plotted with some ease because of the great number of public disputations with heretics which were notable enough to have been mentioned by various chroniclers. The next seven years of Dominic’s life, however, are obscure to the historian, but we know that the Albigensian crusade brought the heresy under complete control.

In the calm of 1215 Foulques, the learned bishop of Toulouse, appointed Dominic and his companions preachers for the diocese of Toulouse.11 It was at this time, when Dominic was 45 years old, that he and his six companions presented themselves to Alexander Stavensby, an English secular master in theology then lecturing in Toulouse. Alexander Stavensby “genere, scientia et fama preclarus,’’12 was later professor at Bologna, member of the papal household and eventually bishop of Coventry and Lichfield.13 Stavensby was thus the first teacher of the new band of preachers which received the confirmation of Pope Honorius III on December 22 of the following year. Dominic understood well the words of Proverbs: “Without knowledge even zeal is not good.” (Prov. 19:2) Henceforth university cities became the centers of his Order’s work. At the first dispersal of the friars in August, 1217, seven of the sixteen were sent to Paris, and early the following year a foundation was made at Bologna.14 In 1220 Dominic sent friars to Palencia and Montpellier to establish houses just as new universities were being founded in those cities. One of Dominic’s last official acts was to send thirteen friars to the university city of Oxford.15

Why did Dominic send his brethren to the university cities? Was it to teach in the growing universities? Obviously not. These original friars at Toulouse, Paris, Bologna, Palencia, Montpellier and Oxford were not masters in theology; hence they could not teach in any university. No, these brethren were sent to centers of learning in order to learn. “Without knowledge even zeal is not good.” Dominic was not only convinced of the importance of learning, but he made it an essential element in his new Order; he made it an essential means of the apostolate. “Study,” wrote Humbert of Romans, “is not the purpose of the Order, but it is of the greatest necessity for the aims we have mentioned, namely, preaching and working for the salvation of souls, for without study we can achieve neither.’’16

Among the early brethren there were a few with arts degrees from various centers of learning. At Paris “many excellent clerics’’17 entered the Order so that when Dominic arrived in 1219 the new priory already numbered thirty members.18 On the other hand, there were many who were uneducated (rudes). Nevertheless all were bound to “the assiduous study of sacred truth”, just as they were bound to the three vows, the common life and the choral office.

Every Dominican priory had to have a rector whose obligation it was to give theological lectures on the Sacred Scriptures to all the brethren.19 Not even the prior was exempt from attendance at these lectures. The degree of Lector in Sacred Theology is nothing more than the authorization of the Order to lecture within Dominican houses. It was not a degree from any university. Later when priories were large, a number of lectors would be assigned to a house, one friar, called the lector primarius was entrusted with supervising all teaching and deciding ail theological disputes. Thus even before the Order had any claim on the University of Paris, that is, before the Order obtained its first Master in Theology, every cleric in the Order was bound to the assiduous study of sacred truth.

The spirit of St. Dominic was understood perfectly by Jordan of Saxony, who was elected to succeed Dominic at the General Chapter of 1222. Jordan, himself a master in arts and a bachelor in theology of the University of Paris, saw clearly the importance of learning in the Order. In all of his travels and preaching he tried to recruit members from university circles.20 In 1228 Jordan brought Roland of Cremona to Paris and had him enrolled in the faculty of theology under John of St. Giles, an English master. Roland was a master in arts from Bologna and he had spent almost ten years in the study of theology before he enrolled at Paris. Jordan indeed must have had considerable influence at Paris, for Roland merely lectured on the Sentences of Peter Lombard for one year before receiving the S.T.M. This was most extraordinary. Roland of Cremona was, in fact, the first Dominican to lecture as a master at the greatest center of Christian learning. In September of the following year (1230) John of St. Giles himself entered the Order, thus giving the Dominicans two chairs at the University of Paris.

Learned men such as Jordan of Saxony, Roland of Cremona Hugh of St. Cher and John of St. Giles, were attracted to the Order because of the spirit of St. Dominic which flourished among the brethren. The primitive constitutions in force during B1. Jordan’s Generalate declare strongly: “The brethren ought to be so intent on study that by day and by night, at home or on a journey, they read or meditate on something, and endeavor to commit to memory whatever they can.’’21One day a man asked Jordan of Saxony what rule of life he followed, apparently he had never before seen the habit. To this query Jordan replied, “The rule of Friars Preachers, and this is their rule: to live virtuously, to learn and to teach (honeste vivere, discere et docere).”22Jordan went on to explain that these are the three blessings David asked of God when he said, Bonitatem et disciplinam et scientiam doce me (Ps. 118:66). Bl. Jordan’s statement of the rule, namely “to live virtuously, to learn and to teach,” is a perfect expression of the mind of St. Dominic in establishing the Order of Preaching Friars.

By the time Humbert of Romans was elected fifth Master General in 1254 the fame of the Order was widespread and the intellectual character of St. Dominic’s Order was solidly established by the growing renown of St. Albert the Great and the promising ability of St. Thomas Aquinas. Humbert of Romans, who first loved the Carthusians and who all his life cherished a strong bent toward asceticism, himself found no difficulty in ranking study as an essential means of the apostolate.23After listing eleven benefits of study Humbert says, “Who is there who knows the reputation of the Friars Preachers, who does not know that these benefits have been produced and are being produced in them from the study of letters? Consequently lovers of that Order are accustomed to be not a little zealous for study in promoting it in the Order.”24

If this is not sufficient to indicate the importance of study in the ideal of St. Dominic, two further indications should confirm the picture already presented.

First, there is the unique feature of the primitive constitutions not found in the statutes of any other religious Order at the time. By this I do not mean the organization of the laws. One anonymous author tells us that before Raymond of Peñafort’s revision (1239) the Dominican constitutions were in a state of utter confusion (que sub multa confusione antea habebantur).25 Raymond merely regrouped the ancient legislation under distinct headings. The format of Raymond’s revision resembles the constitutions of other Canonical Orders of the period. The unique feature of the Dominican constitutions, however, is that they alone made provision for study. The constitutions of Prémontré, St. Victor of Paris, St. Denis of Rheims, the Austin Canons and the Grandmontines do not say a word about study.26 Yet we know that Canons Regular, since they were clerics, did devote considerable time to study and writing. The Dominicans, unlike other Orders, made study an essential part of their rule. Study, therefore, did not have the same importance in other Canonical institutes as it did in the Order of St. Dominic. With the Dominicans learning was not a luxury, but a necessity; the pursuit of learning was not a concession, but an obligation. This new role of study in religious life was necessitated by the special end of the Order, which was the preaching of sacred doctrine.

Another interesting light is thrown upon the place of study in the Order by thirteenth century writings concerning the Order. By the middle of the thirteenth century Dominicans were very conscious of the greatness of their ideal. During the second half of the century there appeared a considerable number of literary works designed to increase devotion and to record the traditions of the Order: ut devotio amplius augeatur and ut cuncti . . . noverint sui status primordia et progressus.27 The Vitae Fratrum or Gerard of Frachet falls into this category. More important, however, are the various big bibliographical lists of illustrious men. These lists combine two aspects of the Order in describing illustrious Dominicans: sanctity and learning.28 These lists of renowned theologians are not simply historical chronicles; they are rather ascetico-scientific works intended to arouse in the reader a deeper appreciation of Dominican tradition. An example of this type of work is the treatise of Stephen of Salanhac (+1291) entitled De Quatuor in Quibus Deus Pracdicatorum Ordinem Insignivit.29 This treatise, which was completed by Bernard Gui early in the fourteenth century, is divided into four parts corresponding to the four marks by which God distinguished the Order of Preachers. The first mark is the greatness of its founder, who was Christlike; the second is the glorious title of Preacher, which is apostolic; the third mark is its illustrious progeny which illuminates the world, and fourth is the excellence and security of its rule of life. In listing the illustrious men of the Order Stephen of Salanhac first describes those who have given their lives for the faith (fratres passi pro fide), then he lists those who have been illustrious in writing and in doctrine (viri illustres in scriptis et doctrinis). Historians today are, of course, very grateful for such reliable catalogues, but medieval readers were expected to be edified by these examples of the Dominican ideal in practice.

Briefly, then, we can say that Dominic had a new conception of religious life. Its purpose was the preaching of sacred doctrine and the salvation of souls. The sublime office of preacher had never before been the goal of any Order. Preaching belonged by divine right to bishops, the authoritative teachers of sacred doctrine. Dominic was given authority to establish preaching as the goal of his Order by the universal bishop of Christendom, the Holy Father. In order to attain such a goal, Dominic took the three means he knew as a Canon Regular, namely solemn vows, regular life with its monastic observances and solemn recitation of the divine office. To these he added the new element of study; this was necessitated by the special goal of preaching. Study, therefore, was the new feature in St. Dominic’s way of life.

II

Lest we read historical facts oblivious of the implications of such a novelty, let us try to analyze the place of study in the ideal of St. Dominic by posing a few questions.

1. What did St. Dominic and the early brethren mean by the word ‘study’? Does study mean simply reading, as one would read a newspaper, a magazine or a best-seller? The Latin verb studere means a pushing forward with effort, or a striving after something with zeal . The Latin word studium means not only ‘study’ or a place of study in the English sense, but very often it has its original sense of ‘zeal’. Therefore the reading of newspapers and magazines is not study. Neither is watching television or listening to a lecture what is meant by study. A lecture may be very helpful for acquiring new ideas or direction in thought. Real study, however, requires the quiet of one’s room or the library. The rule of silence in Dominican houses has always been called “the most holy law” and “foremost of all observances”30 because it is necessary for study as well as for prayer. Studying, therefore, is not to be confused with wide reading, spiritual reading or even with reading the Bible. Wide reading is excellent for acquiring a wide range of information. Spiritual reading is necessary for the spiritual life. Reading the Bible is essential for a Dominican. But study, real study, is the intellectual grappling with truth.

In describing the Dominican rule Jordan of Saxony said discere et docere. Discere, to learn, means to acquire a perception in the manner of a disciple learning new truths; it means to acquire truth from a teacher. The doctrine, or learning which has been thus acquired can then be taught to others. Bl. Jordan’s expression, discere et docere, as the rule of the Dominican Order corresponds perfectly to St. Thomas’ expression: contemplare et contemplata aliis tradere.31 “The highest place among religious orders,” writes St. Thomas, “is held by those which are ordained to teaching and preaching, which functions belong to and participate in the perfection of bishops.”32 Commenting upon this the older Dominican constitutions declare:

Of such type is our Order of Preachers, which from its first foundation is principally, essentially and by name ordained to teaching and preaching, to communicating to others the fruits of contemplation.33

It is clear, then, that the fruits of contemplation which are given to others in Dominican teaching and preaching are none other than those acquired by study, learning, contemplation. The three expressions, studere, discere, and contemplare, designated one and the same reality among Dominicans of the thirteenth century. That reality is the zealous, human effort by which truth is assimilated.

2. What truth, we may ask, is the object of Dominican study? Is it philosophical truth? Is it knowledge of current political affairs, literature or sports? The constitutions are very explicit about this when they declare “the assiduous study of sacred truth.” Sacred truth is the sacra doctrina of divine revelation contained in Sacred Scripture and interpreted by the Church . The prestige of a Master in Sacred Theology and a Preacher General in the thirteenth century is intelligible only in terms of the sacred doctrine which is to be given to others in the apostolate. It has been said34 that the Dominican Order has a transcendental relation to truth, that is, to sacred truth and the Absolute Truth which is God Himself. The Order of Preachers was described by Mechtilde of Magdeburg as “Ordo veritatis lucidae”,35 luminous truth because the object of its study, teaching and preaching is the sacred truth of sacred doctrine.

What, then, about the study of philosophy, the arts and current affairs? The primitive constitutions explicitly forbade the study of philosophy and the liberal arts.

The brethren are not to study the books of classical authors and philosophers, even though they glance at them briefly. They are not to pursue secular learning, not even the liberal arts, unless the Master of the Order or the General Chapter disposes otherwise in certain cases. Rather the brethren both young and old are to study only theological books.36

This legislation is taken almost verbatim from the ancient Church law governing monks.37 In the early days there was no need to study philosophy or the arts in the Order; young men entered already trained in the humanities at the university. St. Albert received his arts training at Padua, St. Thomas at Naples; they were prepared to study theology. By 1259, however, it became evident that youths entering the Order were not sufficiently trained; the new ratio studiorum of 1259 established studia philosophiae in certain provinces corresponding to the university faculty of arts. But even in these houses of philosophy students were required to attend the theology lectures of the lector primarius. In other words, the study of philosophy was considered a necessary means to theology, the study of sacred doctrine.

The principal study of every Dominican cleric in the thirteenth century was theology, even when he was assigned to a studium of logic or natural philosophy. The importance of philosophy for theology cannot be over-estimated. Since the middle of the thirteenth century the Order of Preachers has continually fostered the study of philosophy the sciences and arts — all with a view to sacred doctrine and the apostolate. “Our study,” declare the primitive constitutions, “must aim principally at this, that we might be useful to the souls of others.”

3. Upon whom, however, does this obligation to study rest? It would seem that only those who are assigned by superiors to study have the obligation, for example, students during their years of training and Fathers who are sent on to special studies. Not all Dominicans have the same inclination to study. Thus it would seem that those who can take it should take it. Further, superiors are preoccupied with details of the common good and hence would seem to be exempt from study. It is often said that once a man is elected or appointed superior, his days of study are over. Furthermore, it would seem that brethren who are engaged in the apostolate or parish work or full-time teaching in high schools are too busy to study beyond the immediate needs of class. All things considered, it would appear that only those assigned to study have the leisure or the obligation to study.

Before answering this question one historical point ought to be clarified with regard to actual preaching in the thirteenth century. Every member of the Order in the Middle Ages was technically called a ‘Preacher’, just as every Franciscan was called a ‘Minorite’. But not every Dominican was given the honor of actual preaching. Only specially qualified Fathers were given a mandatum to preach by the Prior, Provincial or General Chapter.38 A preacher thus commissioned was not to be burdened with temporal administration, nor was he to carry anything with him except necessary clothing and books.39 Sermons were also given by Masters in Sacred Theology in the university and curia, preaching was a function proper to masters in theology. But other members of the Order could only prepare themselves for the day when they too might receive the mandate to preach or become a master.

But with regard to the means chosen by St. Dominic for his way of life every Dominican, whether he be superior or subject, teacher or student, preacher or secretary, was obliged to the three solemn vows, to regular life with its monastic observances, to the solemn recitation of divine office, and to the assiduous study of sacred truth. Even the most inept cleric in the Order was bound to assiduous study according to his abilities. The obligation of choral office was not limited to those with good voices; nor was the obligation of common life restricted to the gregarious. Why, then, should we think that the obligation to study fell only on geniuses? Study, therefore, is a universal obligation in the Order as serious in intent as solemn recitation of the divine office and regular observance. In fact, historically and constitutionally study is more important, since from the very beginning of the Order the constitutions readily provided for dispensations from choir and certain observances for the sake of study.40 But they provided no dispensation from study itself.

While it is true that superiors have less time for study than their subjects, this does not relieve them of the obligation to study. In the thirteenth century, we have already noted, priors were held to attend the daily theological lecture of the rector primarius. St. Albert the Great wrote most of his commentaries on Aristotle when he was Provincial of Germany, preacher of the crusades or burdened with the episcopal office. Hugh of St. Cher prepared his monumental work on the Bible while he was an active Cardinal of the Church. Peter of Tarentaise revised his commentary on the Sentences while he was Provincial of France. Hervé Nédélec was most energetic in study and writing during his Provincialate and Generalate. Cajetan was Master General of the Order and Cardinal when he wrote his remarkable commentary on the Summa of St. Thomas. In the thirteenth century Provincials were expected to study sacred doctrine assiduously; commonly they were assigned by the General Chapter to teach theology in a studium after their term of office. There was no doubt, at least before the Reformation, that study was binding upon all Dominicans, lay-Brothers and Sisters excepted. “The brethren,” stated the constitutions, “ought to be so intent on study that by day and night, at home or on a journey, they read or meditate on something, and endeavor to commit to memory whatever they can.’’41

The medieval mind would have found it hard to comprehend the excuse that a Dominican is too busy with the apostolate to study. The argument that a preacher is too busy preaching to pray would have been just as incomprehensible. Mention has already been made of the constitution forbidding preachers to carry anything with them except clothing and books. St. Dominic himself always carried with him the Gospel according to St. Matthew and the Epistles of St. Paul.42 Jordan of Saxony listed books as the first necessity of mendicant preachers.43 The more one is engaged in preaching and the apostolate, the more one needs the light of divine truth, just as he needs the strength of prayer. In the Dominican Order no one is exempt from the assiduous study of divine truth.

The story is told of a certain friar in the early days of the Order who neglected study for the sake of long prayers and works of asceticism. Once he was discovered “the brethren often accused him of making himself useless to the Order by not studying.”44

4. How much, we may ask, should a Dominican study in order to fulfill his constitutional obligations? From what has already been said, no other answer can be given but: Always, according to the dictates of supernatural prudence. Just as we are told by Christ to “pray always and not lose heart” (Luke 18:1), so a Dominican is told by his constitutions to study always without interruption. The primitive constitutions use the expression “by day and night, at home or on a journey”. The modern constitutions express this by the word “assiduous”. The Latin word assiduus means continual, unremitting, incessant, perpetual. For a Dominican there is no time limit to the assiduous study of sacred truth.

The profundity, breadth, care and zeal of St. Albert’s study are apparent on every page of his writings. The prodigious industry of St. Thomas has never ceased to astound later generations; the clarity and precision of his style, the aptness of his quotations, the extent of his sources and the genius of his synthesis all testify to ceaseless study. Describing Cardinal Cajetan, the careful historians, Quétif and Echard, remark:

What is more amazing about Cajetan, however, is his pertinacity in the study of letters, so that no day ever passed without his having written a line whether he was alone or engaged in official duties, whether at home or on a journey, whether as cardinal or legate, free or captive, healthy or sick. This is evident if one examines the lower margin of each of his writings where the place, day, year and current activities are diligently noted. Hence, it is related, he was wont to say that he could hardly excuse from grievous sin a fellow Dominican who failed to devote at least four hours a day to study.45

This strong statement attributed to Cajetan indicates the seriousness of study in the Dominican Order. It is an obligation arising not from Holy Orders, but from the solemn vow to live according to the rule and constitutions of the Order. Contempt for study amounts to contempt of the constitutions. Neglect of study in the Order is neglect of sanctity. Every Dominican, therefore, has an obligation not binding on secular priests, monks or other religious. This is the obligation to study without ceasing.

In discussing the frequency of prayer St. Thomas distinguishes between prayer itself and the root of prayer.46 Prayer arises from the desire of charity, which desire must be within us continually either actually or habitually. Actual prayer, however cannot be continual (assiduus) because of other necessities. Similarly it can be said that for a Dominican study must be assiduous in its root, which is desire for the ideal of St. Dominic. Actual study cannot be assiduous or unremitting because of other necessities. The amount of actual study every day must be determined by the ideal of St. Dominic and daily necessities.

A learned Dominican of the last century, Fr. Alberto Guglielmotti, used to say to his novices, “A true Dominican ought to die at his desk or in the pulpit.”47 Fr. Guglielmotti himself died fittingly at his desk on September 29, 1893.

5. One final question must be asked before we have a complete picture of study in the ideal of St. Dominic. What about sanctity? The picture presented thus far seems to imply that study is more important than sanctity in the Order of Preachers. Not at all. Sanctity is the common goal of all the faithful and of all religious. Striving for sanctity is not peculiar to any one religious community or rule. The way in which one organization strives for sanctity is established in the rule and constitutions officially approved by the Church. There are many religious communities in the Church, each with its own goal to achieve and rule of life directed to that goal. Individual members attain sanctity by fidelity to the goal and the way of life. In other words, sanctity is the goal of every religious, but the manner of attaining sanctity is peculiar to a particular rule of life. Sanctity is attained by fidelity to the rule over and above the ordinary means established for all the faithful.

Sanctity for a Dominican is attained through the rule of life proper to the Order of Preachers, that is, through the goal of preaching and the four means specified in the constitutions. A Dominican, therefore, cannot progress in sanctity except through his vows, the solemn recitation of divine office, regular life with its monastic observances, and assiduous study of sacred truth.

Beginners in the Dominican way of life not uncommonly experience a conflict between the desire for prayer and the obligation of study. Sometimes there seems to be an opposition between the spiritual life and the intellectual life of an individual. Patience, perseverance, meditation and the study of theology, however, gradually unite the disparate impressions into a single ideal, the ideal seen and loved by St. Dominic himself. This ideal is so sublimely one that no aspect can be neglected without losing the whole. The ideal of St. Dominic was beautifully described by God the Father in a dialogue with St. Catherine of Siena:

Look at the ship of thy father Dominic, My beloved son: he ordered it most perfectly, wishing that his sons should apply themselves only to My honor and the salvation of souls, with the light of science, which light he laid as his principal foundation, not, however, on that account, being deprived of true and voluntary poverty, but having it also…. But for his more immediate and personal object he took the light of science in order to extirpate the errors which had arisen in his time, thus taking on him the office of My only-begotten Son, the Word.48

Learning is so important for a Dominican that he might well fear the words of the Prophet Osee: “Because thou hast rejected knowledge, I will reject thee, that thou shalt not do the office of priesthood to me.”49

[important]

NOTES

1 Constitutiones FFr S.O.P., ed. iussu M.S. Gillet (Rome 1932), I, I, 3, 1. All translations here and elsewhere in this paper are my own, unless qxplicitly stated otherwise.

2 Constitutiones Antiquae Ordinis Fratrum Pracdicatorum (1228), Prol. ed H. Denifle in Archiv f. Lit.-u. Kirchengeschichte, I (Berlin 1885), p.

3 Const. FFr. S.O.P., ed. cit., I, I, 4, 1.

4 P. Mandonnet, Saint Dominique, l’idée, l’homme, et l’oeuvre. 2nd ed. (Paris 1987), II, p. 99.

5 Jordan of Saxony, Libellus de principiis, n. 6 (MOPH, XVI, p. 28).

6 Ibid., n. 7.

7 Acta canonizationis, n. 35 (MOPH, XVI, p. 158).

8 Ibid., n. 35 (p. 154), Jordan, Libellus, n. 10, ed cit. p. 31.

9 Anon., Vita Beati Dominici (before 1260), ed. Analecta Ord Praed. IV (1899), p. 299b.

10 Jordan, Libellus, n. 15, ed. cit., pp. 33-34, Humbert of Romans Legenda S. Dominici, n. 11 (MOPH, XVI, p. 377).

11 Jordan, Libellus, nn. 39-43, ed. cit., pp. 45-46. Cf. P. Mandonnet op. cit., II, p. 44. The official document constituting Dominic and his companions preachers in the diocese of Toulouse is published by M. H. Laurent, O.P., Monumenta Historica S.P.N. Dominici, (MOPH, XV), n. 60

12 Humbert of Romans, Legenda, n. 40, ed. cit., p. 400.

13 Conrad Eubel, O.S.B., Hierarchia Catholica Medii Aevi, 2nd ed. (Munich 1913), I, p. 207, A. Potthast, Regesta Pontificum Romanorum (Berlin 1874), I, n. 7223/24, p. 624.

14 Jordan, Libellus, n. 51 ed. cit., p. 49-50

15 Nicholas Trivet, Annales sex regum Angliae, 1135-1307, ed. T. Hog (London: English Historical Society, 1845), p. 209. Cf. W. A. Hinnebusch O.P., The Early English Friars Preachers, (Rome: Dissertationes Historicae, XIV, 1951), pp. 1-10 and 333.

16 Humbert of Romans, De Vita Regulari, Prol., n. 12, in Opera, ed. J. J. Berthier, O.P., I (Rome 1889), D. 41

17 Acta Canonizationis, n. 26, ed. cit., p. 144.

18 Jordan, Libellus, n. 59, ed. cit., p. 53.

19 Constitutiones Antiquae, Dist. II, cap. 23, ed. cit., Archiv, I, p. 221. Cf. revised constitutions of Raymond of Peñafort, Dist. II, cap. I, ed. R. Creytens, O.P, “Les Constitutions des Freres Precheurs dans la Rédaction de s. Raymond de Peñafort (1241),” in Archioum FFr. Praed., XVIII (1948) 48. Humbert, speaking of the office of Prior, notes his obligations: “pro religone primo, et pro studio secundo, plusquam pro aliis quibuscumque zealare…. Spiritualibus quoque exercitus intra claustrum, ut sunt scholae, collationes, sermones, officium divinum, et huiusmodi, libenter interesse.” De Officiis Ordinis, cap. III, Opera, ed. cit., II, p. 202.

20 See the history of the Friars Preachers by Fr. W. A. Hinnebusch, O.P., chapter XXV, sect. 2: “Dominican Recruiting in University Circles.”

21 Constitutiones Antiquae, Dist. I, cap. 13, ed. cit., Archiv, I, p. 201. Constitutions of Raymond, Dist. II, cap. 14, ed. cit., p. 66.

22 Gerard of Frachet, Vitae Fratrum, P. III, cap. 42, 8, ed. B. M. Reichert, O.P. (MOPH, I, p. 138).

23 See Fr. Hinnebusch’s history of the Order, chapter XXV sect. 1: “Dominic’s Attitude Toward Learning.”

24 Humbert of Romans, Expositio Regulae B. Augustini, cap. 4, n. 143 in Opera, ed. cit., I, p. 435.

25 Cronica Ordinis, annotation for 1238 (MOPH, I, p. 331). See the critical study of Raymond’s revision by R. Creytens, O.P., op. cit., Archicum FFr. Praed., XVIII (1948), 5-28.

26 Edmund Martène, O.S.B., De Antiquis Ecclesiae Ritibus, Antwerp 1764. The rule of St. Victor of Paris (III, pp. 252-291), St. Denis of Rheims (III, pp. 297- 302) Austin Canons (III, pp. 306- 320), Premonstratensians (III, pp. 323-336), Grandmontines (IV, pp. 308-319).

27 H. Denifle, O.P., “Queller zur Gelehrtengeschichte des Predigerordens im 13. und 14. Jahrhundert,” in Archiv f. Lit.-u. Kirchengeschichte d. Mittelalters, II (Berlin 1886), 165 248. See the letter of Bernard Gui to the Master General, Aymeric, dated 22 Dec. 1304, in which the purpose of Stephen of Salanhac’s work is stated. De Quatuor in Quibus Deus Praedicatorum Ordinem Insignivit, ed. T. Kappeli, O.P., (MOPH, XXII, p. 8).

28 P. Auer, O.S.B., Ein Neuaufgafundener Katalog der Dominikaner Schriftsteller (S. Sabinae, Dissert. Hist., II), Paris 1933, pp. 2-7.

29 Edited by T. Kappeli, O.P., in MOPH, XXII (Rome 1949).

30 Constitutiones FFr. S.O.P., IV, I, 4, 5, 1.

31 St. Thomas, Sum. Theol., II-II, q. 188, a. 6.

32 Ibid.

33 Constitutiones, ed. iussu A. V. Jandel, Prol., Decl. I, n. 13, (Paris 1872), p. 16.

34 Ernst Commer, “Die Stellung des Predigerordens in der Kirche und seine Aufgaben,” Divus Thomas, III (1916), 445-7.

35 Revelationes Gertrudianae ac Mechtildianae, II (Paris 1877), p. 528, quoted by Angelo Walz, O.P., in his San Tommaso d’Aquino, (Rome 1945), p. 92, and in his Compendium Historiae Ordinis Pracdicatorum, rev. ed. (Rome 1948), p. 28.

36 “In libris gentilium et philosophorum non studeant, etsi ad horam inspiciant. Seculares sciencias non addiscant, nec etiam artes quas liberales vocant, nisi aliquando circa aliquos magister ordinis vel capitulum generale voluerit aliter dispensare, sed tantum libros theologicos tam juvenes quam alii legant.” Constitutiones Antiquae, Dist. II, cap. 28, ed. cit., Archiv, I, p. 222.

37 Regula monachorum, c. 8 (PL 83, 877-8). Cf. Gratian, Decretum, Dist. XXXVII, in Corpus Iuris Canonici, Pars Prior: Decretum Gratiani, ed. A. Friedberg (Leipzig 1924), col. 135-140. Se the excellent article by G. G. Meersseman, O.., “In libris gentilium non studeant. L’étude des classiques interdite aux clercs au moyen age?” in Italia Medioevale e Umanistica, I (1958), 1-13.

38 Constitutiones Antiquae, Dist. II, cap. 20 and cap. 32, ed. cit., pp. 219- 220 and 224; revision of Raymond, Dist. II, cap. 12, ed. cit., pp. 63-4.

39 Constitutiones Antiquae, Dist. II, cap. 31, ed. cit., p. 223, revision of Raymond, Dist. II, cap. 13, ed. cit., p. 64.

40 Constitutiones Antiquae, Dist. II. can. 29, ed. cit., p. 223, revision of Raymond, Prol. and Dist. II, cap. 14, ea. cit., pp. 29 and 67.

41 Constitutiones Antiquae, Dist. I, cap. 13, ed. cit., p. 201; Raymond, Dist. II, cap. 14, ed. cit., p. 66.

42 Acta Canonizationis, n. 29, ed. cit., p. 147.

43 Jordan, Libellus, n. 89, ed. cit., p. 45.

44 Gerard of Frachet, Vitae Fratrum, P. IV, cap. 5, 2, ed. cit., p. 161.

45 “. . . Unde fertur dicere solitum, sodalem Praedicatorum vix se a peccato mortali excusare, qui quoto die quatuor horas studio non impenderit.” Quétif- Echard, Scriptores Ord. Praed. (Paris 1722), II, p. 16a.

46 St. Thomas, Sum. Theol., II-II, q. 88, a. 14.

47 Il Rosario — Memorie Domenicane, 1912 p. 466; 1918 p. 481 ff.

48 The Dialogue of St. Catherine of Siena, chap. 158 (in Ital. ed. of I, Taurisano O.P., Rome 1941), trans. by Algar Thorold (Westminster, Maryland 1943), p. 298.

49 Osee 4:6 Cf. St. Thomas, In III Sent., dist. 25, q. 2, a. 1, sol. 3 ad 3.

[/important]

Reading List

Dominicana

Ch 1 (What is a Dominican?)

Ch 2 (The Four Pillars)

St. Dominic

Ch 1

Articles(available on website)

Can Dominicans Really Be Lay People?

The Dominican Difference in the World

Suggested:

Sacred Scripture

Gospel of St Matthew Ch. 1 – 16

Catechism of the Catholic Church

Introduction

Paragraphs 1 – 248

Reading List Notes

Every month you will have assigned readings in Scriptures, the Catechism, and sometimes other books to complete. It is suggested that you do some of the readings every day. You may do them as you wish. In the Appendix section there are suggested daily readings from Scriptures and the Catechism which will correspond to the Reading List for the month. Remember that the Scripture and Catechism readings are recommended and not required. Also all answers to the questions must be written and brought to the monthly meeting.

“Am I Saving the World Yet?”

by Br. Vincent Ferrer Bagan, OP

Being a student can be frustrating.

I recently read an article by Emily Stimpson over at Our Sunday Visitor about millennial Catholics. Citing a study suggesting that large numbers of Catholics in my generation are losing their faith, Stimpson highlights the encouraging fact that, of those who are not losing their faith, many are dedicating their lives to spreading it. She goes on to profile six of these young, faithful Catholics, and it was inspiring to read their stories.

As I read the article, I thought to myself, these people are really making a difference; they are, in a very real way, reaching out to their brothers and sisters and bringing them the beauty of the Gospel. This is exactly why I entered the Order of Preachers, but it seems a far cry from what I’m doing now. This summer, I’m spending my afternoons in Spanish class and my evenings watching a sappy (but, for that reason, quite entertaining) Spanish-language series called Destinos. In addition to study and prayer, I spend most of my time in our priory doing various things in support of our liturgical and communal life. Is the work I’m doing really helping the cause of preaching the Gospel for the salvation of souls? Is it really achieving the end that motivated me in the first place?

It is tempting for those of us who are students, or who are in some sort of training or formation program, to answer this question in the negative. We may have a theoretical understanding of how our work is ordered to our mission, but, practically speaking, the connection often seems tenuous. I propose three reasons, however, that we can and should see a deep connection between prayerful study and the goal of spreading the Gospel.

First, it is important to remember that the ultimate goal of our lives is not apostolic productivity, but union with God. If we want this union, we must spend time coming to know Him through prayer and study. These things are not useful by the world’s standards, but are indispensable to our true ultimate goal.

Second, the most effective foundation for a fruitful apostolate is a life of prayer and study as well as faithfulness to the day-to-day responsibilities that God, in His providence, has placed before us. If we do all that we can to know and love God ourselves, we will be well prepared to share the beauty of his truth and his love with others. Though careful planning and technique are certainly important in the apostolic mission, our efforts will be fruitless if they are not rooted in an abiding knowledge and love of God.

This priority is clearly evident in the following passage from Deuteronomy, which is known as the shema and is treasured by Jews and Christians alike:

Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God is one Lord; and you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might. And these words which I command you this day shall be upon your heart; and you shall teach them diligently to your children, and shall talk of them when you sit in your house, and when you walk by the way, and when you lie down, and when you rise (Dt 6:4–7).

Before we speak of God to others, we must know and love him ourselves with the entirety of our being. This is not to say, of course, that we should wait until we are perfect to speak of God, but rather that the apostolate must be built on the foundation of the knowledge and love of God. Third, I offer one of our Dominican mottoes: “to contemplate and to hand on to others the fruits of contemplation.” Time spent in prayer, study, and fostering virtue provides not only the foundation, but also the content, for an effective apostolate. Especially in a time when the general currents of intellectual life and social mores run contrary to the Gospel, it is important that we be able to articulate the truths of the faith in a compelling way, from the knowledge of God acquired in prayer and study. This is precisely what we cultivate during periods of religious and academic formation, when we cannot be fully active in the work of the apostolate.

At such times we must trust in God’s providence—trust that if we are faithful in attending to the tasks and the people God has placed before us, He will use us, perhaps in ways we will never know, for the building up of his kingdom.

Questions:

Reminder: Try taking the twelve Pillars of Dominican Laity/Nine Ways of Prayer to Adoration during this year. Contemplate on these as a “way of life.”

- Can Study as a pillar of Dominican life further my relationship with God and help deepen it? Explain.

- Give brief thoughts on the quote: “Neglect of study in the Order is a neglect of sanctity.”

Dominicana: A Guidebook for Inquirers

Ch. 1 (What is a Dominican?)

- Write a few thoughts on Saint Dominic’s life. How can you see yourself as his follower?

- Why is correct formation so important?

- What is the worldwide family of Order of Preachers made up of?

- What are the three major aspects of the formation of Lay Dominicans? Explain which one will be the most challenging for you?

Ch. 2 (The Four Pillars)

- How are the four pillars interconnected? Which one pillar if the foundation of the other pillars?

- What is the principle prayer of the Order? Name another prayer that Dominicans are devoted to?

- Describe Dominican study compared to merely acquisition of knowledge?

- What is the connection between the Dominicans and the orthodoxy of the Church?

- How can I increase my opportunities to Dominican Study?

Meeting 2

The Pillars of Dominican Life:

Community Life

Community life is of key importance to all Dominicans. It is in fact, one of the pillars of Dominican life. For the members of the First, Second and Third Order Religious it means a group of men or women leading a common life according to a rule. It can be difficult when personalities clash, irritations and frustrations can create friction and tension, human failings and individualities can cause hurt, disappointments and heartaches. But, on the other hand, a community can also provide an immense source of strength.

Living in community demands sacrifice, the ability to ignore one’s own personal desires, concessions to others, maintaining quiet and calm when one desires emoting, but there are rewards – the inspiration provided by one’s brothers and sisters in St. Dominic, companionship, help and concern and, most of all, love, greatly outweigh the disadvantages.

You, as lay Dominicans, will not live in such close quarters as those who belong to the Friars, Nuns and Sisters communities, and yet a chapter is a very real community. We are members of the same family, brothers and sisters in St. Dominic, and we have a common goal, purpose and mission. The chapter is our community, the place to which we have been called to be members.

In a very real sense, we are similar to the early Christian communities to whom St. Paul wrote his letters. They did not live under the same roof either. They met occasionally – once a week as rule for the Eucharist when conditions permitted. Persecution, lack of priests and barbarian invasions would often hinder them. It might be helpful to recall some of his exhortations to those communities and apply them to ourselves.

To the Romans he wrote:

“Love one another in mutual affection; anticipate one another in showing honor. Do not grow slack in zeal, be fervent in spirit, serve the Lord. Rejoice in hope, endure in affliction, persevere in prayer. Contribute to the needs of the holy ones, exercise hospitality. (Rom. 12: 10-13)”

He told the Galatians:

“Bear one another’s burdens and so you will fulfill the law of Christ. (Gal. 6: 2)”

He urged the Philippians:

“Complete my joy by being of the same mind, with the same love, united in heart, thinking one thing. Do nothing out of selfishness or out of vainglory; rather, humbly regard others as more important than yourselves, each looking out not for his own interests, but also everyone for those of others. (Phil. 2: 2 & 3)”

One of the more beautiful passage is to be found in the Letter to the Colossians:

“Put on then, as God’s chosen ones, holy and beloved, heartfelt compassion, kindness, humility, gentleness, and patience, bearing with one another and forgiving one another if one has a grievance against another; as the Lord has forgiven you, so must you also do. And over all these put on love, which binds the rest together and makes them perfect. (Col. 3: 12-14)”

When we analyze these passages we can see that love should be the hallmark of a Christian community, a love which expresses itself in affection, giving honor, acting with humility, compassion, kindness, gentleness and patience. If conflicts arise, all should be quick to forgive. It is the kind of community that requires concessions, the giving up of personal likes and dislikes, having no axes to grind and hanging in when things do not go as the individual would like. The great reward is that it is a school of love.

St. Paul based these exhortations on the fact that all Christians were bound together as members of the one body of Christ. In our communities, our chapters, you are not only bound in that way, you are also bound together as brothers and sisters in St. Dominic, so that everything St. Paul said about those communities holds doubly true for you.

Our Rule and Particular Directory list ways, such as uniting in our common love of God and sharing it in the Eucharist and prayer in common, study, giving service to others, mutual support, tenderness toward those in pain or sorrow and a special concern for our deceased members.

This brings out the idea that the chapter, our Dominican community, should be something more than just a meeting to attend. Attendance at the meetings is tremendously important for us to develop these qualities. Another aspect is that without each member’s presence we are less than we should be or could be. We are deprived of that important element only you have to share with us. In other words, you need us, but we also need you; we need one another.

Any chapter that has been established for a number of years will have members who, because of age or infirmity, cannot come any longer to the regular meetings. They become what we call prayer members. They are important to the chapter because they pray for its growth, vitality and development. As St. Dominic recognized when he founded the cloistered nuns, their prayer was essential if the work of those out on the lines was to be fruitful. Each chapter should have some way of keeping in contact with those people who in past years contributed so much to it, whether it is an individual or a group that telephones or visits these prayer members on a regular basis.

But a sense of community means more than a concern for those who cannot come to the meetings. It also means a care and concern for those who attend. One-way of doing that is to have a portion of our meetings devoted to a sharing of the chapter’s individual’s needs, concerns, problems and sorrows and requests for prayer. Members should also share joys and special blessings and ask that all join in thanking God.

This helps members to get to know one another as brothers and sisters. Another way is community recreation which the Friars have found to be essential to their lives in community. One simple thing the Laity can do is is to share coffee and cookies (or more) at the meetings and, occasionally, a dinner to help to foster a sense of community and togetherness. All this is just as essential for community life for the Laity as it is with the Friars.

Over and above the individual chapters, there is the larger, Provincial, unit with a Provincial Promoter and a Provincial Council that meets at least once a year to bring a sense of cohesiveness to all the chapters – a sense that each chapter is part of a larger family. It is a means of sharing ideas, programs and activities. There are also national or regional meetings and the Laity, like the Friars, are a global organization, and periodically there are world meetings of Lay Dominicans. These gatherings help to make the point that all us are part of the same family, the Dominican Family – all of us, Friars, nuns, sisters and laity, are brothers and sisters in St. Dominic.

DE PROFUNDIS

Psalm 130 (129)

Choir alternates beginning on the superior’s side. We will do this at the first meeting.

Superior: Out of the depths I cry to you, O Lord:

Superior choir: Lord, hear my voice.

Opposite choir: Let your ears be attentive/

to the voice of my supplication.

If you, O Lord, will mark iniquities,/

Lord, who shall stand it?

For with you there is merciful forgiveness;/

And by reason of your law I have waited

for you, O Lord.

My soul has relied on his word;/

my soul has hoped in the Lord.

From the morning watch even until night,/

let Israel hope in the Lord.

Because with the Lord there is mercy,/

and with him plentiful redemption.

And he shall redeem Israel/

from all its iniquities.

Eternal rest grant unto them, O Lord,/

and let perpetual light shine upon them.

From the gate of hell,

Deliver their souls, O Lord.

O Lord, hear my prayer.

And let my cry come unto you.

All: Let us pray./ O God, the Creator and Redeemer

of all the faithful,/ give to the souls of your servants

and handmaids the remission of all sins,/ that through pious supplication/

they may obtain the pardon they have ever wished for./

Who lives and reigns with God the Father/ in the unity of the Holy Spirit,

God, for ever and ever. Amen.

Superior: May they rest in peace.

All: Amen.

SACROSANCTUM CONCILIUM

Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy

Second Vatican Council

SOLEMNLY PROMULGATED BY HIS HOLINESS

POPE PAUL VI

ON DECEMBER 4, 1963

Excerpt

CHAPTER IV: THE DIVINE OFFICE

83. Christ Jesus, high priest of the new and eternal covenant, taking human nature, introduced into this earthly exile that hymn which is sung throughout all ages in the halls of heaven. He joins the entire community of mankind to Himself, associating it with His own singing of this canticle of divine praise.

For he continues His priestly work through the agency of His Church, which is ceaselessly engaged in praising the Lord and interceding for the salvation of the whole world. She does this, not only by celebrating the Eucharist, but also in other ways, especially by praying the divine office.

84. By tradition going back to early Christian times, the divine office is devised so that the whole course of the day and night is made holy by the praises of God. Therefore, when this wonderful song of praise is rightly performed by priests and others who are deputed for this purpose by the Church’s ordinance, or by the faithful praying together with the priest in the approved form, then it is truly the voice of the bride addressed to her bridegroom; lt is the very prayer which Christ Himself, together with His body, addresses to the Father.

85. Hence all who render this service are not only fulfilling a duty of the Church, but also are sharing in the greatest honor of Christ’s spouse, for by offering these praises to God they are standing before God’s throne in the name of the Church their Mother.

86. Priests who are engaged in the sacred pastoral ministry will offer the praises of the hours with greater fervor the more vividly they realize that they must heed St. Paul’s exhortation: “Pray without ceasing” (1 Thess. 5:11). For the work in which they labor will effect nothing and bring forth no fruit except by the power of the Lord who said: “Without me you can do nothing” (John 15: 5). That is why the apostles, instituting deacons, said: “We will devote ourselves to prayer and to the ministry of the word” (Acts 6:4).

87. In order that the divine office may be better and more perfectly prayed in existing circumstances, whether by priests or by other members of the Church, the sacred Council, carrying further the restoration already so happily begun by the Apostolic See, has seen fit to decree as follows concerning the office of the Roman rite.

88. Because the purpose of the office is to sanctify the day, the traditional sequence of the hours is to be restored so that once again they may be genuinely related to the time of the day when they are prayed, as far as this may be possible. Moreover, it will be necessary to take into account the modern conditions in which daily life has to be lived, especially by those who are called to labor in apostolic works.

89. Therefore, when the office is revised, these norms are to be observed:

a) By the venerable tradition of the universal Church, Lauds as morning prayer and Vespers as evening prayer are the two hinges on which the daily office turns; hence they are to be considered as the chief hours and are to be celebrated as such.

b) Compline is to be drawn up so that it will be a suitable prayer for the end of the day.

c) The hour known as Matins, although it should retain the character of nocturnal praise when celebrated in choir, shall be adapted so that it may be recited at any hour of the day; it shall be made up of fewer psalms and longer readings.

d) The hour of Prime is to be suppressed.

e) In choir the hours of Terce, Sext, and None are to be observed. But outside choir it will be lawful to select any one of these three, according to the respective time of the day.

90. The divine office, because it is the public prayer of the Church, is a source of piety, and nourishment for personal prayer. And therefore priests and all others who take part in the divine office are earnestly exhorted in the Lord to attune their minds to their voices when praying it. The better to achieve this, let them take steps to improve their understanding of the liturgy and of the bible, especially of the psalms.

In revising the Roman office, its ancient and venerable treasures are to be so adapted that all those to whom they are handed on may more extensively and easily draw profit from them.

91. So that it may really be possible in practice to observe the course of the hours proposed in Art. 89, the psalms are no longer to be distributed throughout one week, but through some longer period of time.

The work of revising the Psalter, already happily begun, is to be finished as soon as possible, and is to take into account the style of Christian Latin, the liturgical use of psalms, also when sung, and the entire tradition of the Latin Church.

92. As regards the readings, the following shall be observed:

a) Readings from sacred scripture shall be arranged so that the riches of God’s word may be easily accessible in more abundant measure.

b) Readings excerpted from the works of the fathers, doctors, and ecclesiastical writers shall be better selected.

c) The accounts of martyrdom or the lives of the saints are to accord with the facts of history.

93. To whatever extent may seem desirable, the hymns are to be restored to their original form, and whatever smacks of mythology or ill accords with Christian piety is to be removed or changed. Also, as occasion may arise, let other selections from the treasury of hymns be incorporated.

94. That the day may be truly sanctified, and that the hours themselves may be recited with spiritual advantage, it is best that each of them be prayed at a time, which most closely corresponds with its true canonical time.

95. Communities obliged to choral office are bound to celebrate the office in choir every day in addition to the conventual Mass. In particular:

a) Orders of canons, of monks and of nuns, and of other regulars bound by law or constitutions to choral office must celebrate the entire office.

b) Cathedral or collegiate chapters are bound to recite those parts of the office imposed on them by general or particular law.

c) All members of the above communities who are in major orders or who are solemnly professed, except for lay brothers, are bound to recite individually those canonical hours, which they do not pray in choir.

96. Clerics not bound to office in choir, if they are in major orders, are bound to pray the entire office every day, either in common or individually, as laid down in Art. 89.

97. Appropriate instances are to be defined by the rubrics in which a liturgical service may be substituted for the divine office.

In particular cases, and for a just reason, ordinaries can dispense their subjects wholly or in part from the obligation of reciting the divine office, or may commute the obligation.